The Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission report is Beveridge-like in its ambition. But it is very long (190 pages) and arguably not helped by the relentless talk about beauty which occupies large chunks of its first 52 pages. I have therefore compressed its key points into 3 ½ pages as an aide-memoire.

At the report’s heart is a pincer-like approach to the different elements of our construction, architectural training and planning systems and a wealth of suggestions for fixing the (diverse and complex) structural impediments which now make it difficult to build well in Britain. The core thrust, somewhat concealed, is to graft a continental-style plan-based system onto the UK’s entirely different system of so-called ‘development control’ which is based on permissioning individual buildings.

The report divides itself into 8 proposals or themes, as follows (titles rephrased for clarity, with original headers underneath reference):

- We should move to a more plan-based system

- …with a stronger democratic input

- Long-term stewardship by developers should be incentivised

- Regeneration of older buildings should be encouraged by tax changes; regeneration in general should be oriented to building a ‘sense of place’ through a Minister of Place and other measures

- Urban neighbourhood densification should be encouraged by relaxing some standards

- Greenery should be encouraged

- The education of planners, architects, transport planners etc should be reformed to promote a wider understanding of placemaking

- The planning system should be better resourced

Proposals are numbered for ease of reference to the original document

(The original phrasing was:)

1] We should move to a more plan based system, with 2] a stronger democratic input:

Councils should be required by the NPPF to masterplan (PP5) and be encouraged to do so on an area basis, not just site-by-site, within the context of a redefinition of the aim of the planning system to include ‘achieving beautiful places’ (PP1).

Local authorities should be encouraged to produce detailed design codes (PP6) which define publicly, visually and quantitatively the form, density and standards of development allowed in specific areas. Several alternative forms of codes are suggested, but one option (following Prof Matthew Cardoma) is that codes should include four elements – community and land use; landscape setting; movement; and built form/massing issues. Authorities could be helped by the publication of a National Model Design Code (PP7) from which they could lift designs and ideas.

Local plans should be informed by engagement with residents on local preferences and desires using a nationally recognised process for co-design, and should embody these discoveries in their design codes (PP4, PP11). Local authorities should discover empirically what beauty means to members of their community and what the local ‘spirit of place’ is considered to be.

“This agreed process would make planmaking much more accessible to non-professionals and facilitate the transfer of best practice across the country (PP11).”

Developers should also be required to demonstrate how proposals have evolved as a result of local feedback.

This will all be easier if plans are made digital (PP12).

This shift towards a plan-based system will speed approval of planning applications (PP9):

“If a robust design policy, which is based on community engagement and which has been properly examined, has been established, the detailed planning application stage should be relatively straightforward. The focus should be on compliance with the site-specific design policy, whether contained in the local plan or in a supplementary planning document.”

This in turn (PP10) requires beefed-up enforcement powers to ensure developers follow the plan, and could be supplemented by involving enforcement officers in early discussions about any scheme.

Suburban intensification should similarly be facilitated by the development of street consent mechanisms for codes allowing, eg, extra floors, if there is a majority approval in the street (PP14).

Permitted development rights, which are now causing unacceptably low-quality outcomes, should have standards (PP8).

These local thrusts should be backed by National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) explicitly stressing ‘placemaking’ and ‘the creation of beautiful places’ (PP1), and development should be required not only to produce ‘no net harm’ but to produce a net gain (PP2), presumably so that local authority decision-makers feel empowered to take beauty into consideration when accepting or rejecting proposals. Refusal of ugly schemes should be publicised; the Planning Inspectorate should have a consistent message about placemaking (PP3).

The National Design Guide (2019) should be more visual, and (one has to say it) more conventional, stressing a hierarchy of squares, streets, and green spaces.

3] Long-term stewardship should be encouraged

Higher quality developments would be encouraged if developers retained control of large sites long-term, rather than merely building and selling (PP15).

This requires a change in tax policy (PP17), since a “long-term hold” strategy tends to produce income taxed at 40% and to incur inheritance tax risks, whereas a “build-and-sell” policy is taxed as capital gains at (at most) 20%, and may get entrepreneurs relief and other tax advantages.

Other ideas are the creation of a ‘Stewardship Kitemark’ (PP15) for good-quality long-term developers, and a patient capital fund financed by the public sector to invest in developers who earn the ‘Stewardship Kitemark’ (PP16).

4] Regeneration of older buildings should be encouraged; regeneration in general should be oriented to building a ‘sense of place’

The tax policy on building new places and re-conditioning old places should be equalised (PP23). New buildings are not now charged VAT, while VAT is charged at 20% on repair, maintenance and adaptation of existing buildings. Obviously, this discourages reconditioning existing buildings.

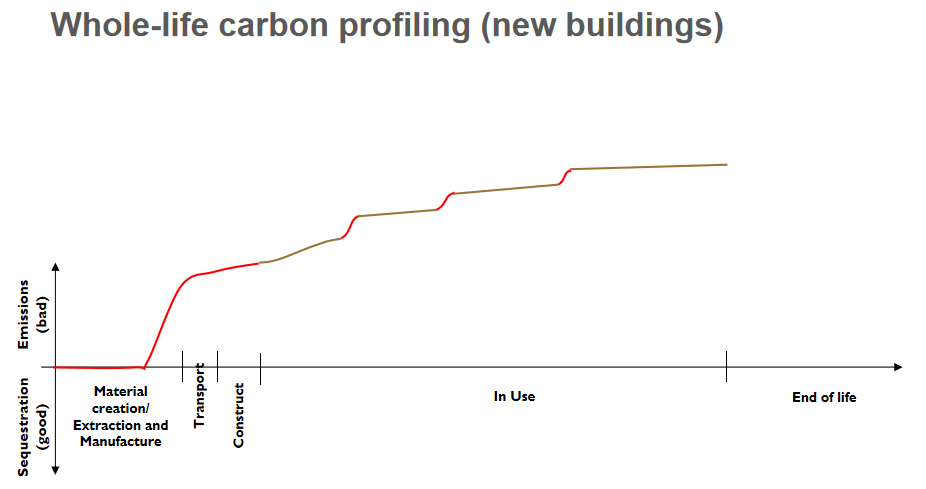

New buildings should be required to submit to an adaptability test (PP24) to ensure that longevity is built in.

A Minister for Place should be appointed (PP20); as well as Chief Place Makers in all authorities (PP21); Regeneration should be re-oriented to being place-led (PP22); Measures should be taken to revitalise high streets (PP25) and to re-orient ‘boxland’ to housing (PP26)

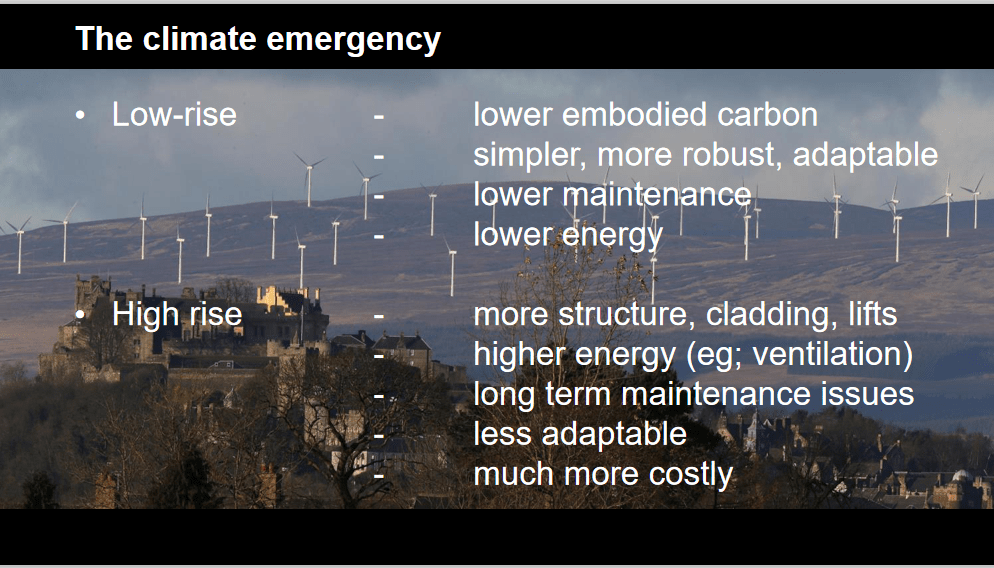

5] Neighbourhood densification should be encouraged

To revive the tradition of building tall dense houses in city centres, some relaxation of standards may be required (PP27):

- encourage councils to require lifts only in a proportion of cases

- discourage minimum back-to-back or front-to-front requirements

- reduce daylight and sunlight requirements

- discourage councils from imposing minimum parking space requirements

National policy framework for healthy streets (PP28) – upgrade the Manual for Streets and make it policy, not guidance (PP29); Various measures to support car-free towns, tougher emission standards, etc

6] Greenery should be encouraged

There should be more emphasis in the NPPF on greenery (PP30); two million new street trees to be planted (PP31); urban orchards encouraged (PP32); and re-greening of streets (PP33).

7] Education should promote a wider understanding of placemaking (PP34).

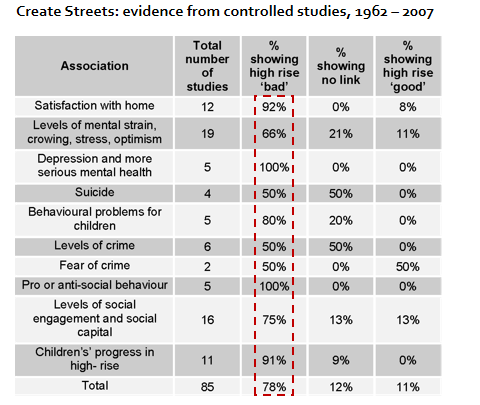

Councillors on planning committees should be given short courses on urban design, well-being, sustainability and public preferences. Planning officers and highway engineers should be trained in place design, and in public preferences and engagement, funded by government. A central component of all courses in architecture, planning and other built environment qualifications should be empirical research on the relationship between urban design and well-being, health and sustainability, as well as public visual preferences and preferences on urban form, (PP35). Design reviews should be encouraged, with a proliferation of competing bodies encouraged (PP36).

8] Planning needs to be better resourced (PP37)

….particularly during the shift to strategic planning which BBBB envisages. It needs to be digitized. Planning centres of excellence need to be created (PP39). The length of planning applications needs limiting (PP38).

Homes England needs to stop judging developments primarily on price, and emphasize design quality and sustainability in weighting scoring (PP41, 42); its targets need to be made more long-term; it needs to be encouraged to take a more master-developer role using form-based codes (PP43). Public sector buildings similarly need to be encouraged to demonstrate civic pride (PP44).

Conclusion: Despite problems of length and style and some curiously unrealistic suggestions, like the suggestion that Chief Place Makers be appointed in all authorities, or the detail required in the National Model Design Code, or the suggestion that every new home should have access to a fruit tree, the report seems to hit many nails on the head.

The problem is that such fundamental reforms require a lot of political support. Beveridge caught the tide of history, and as World War 11 ended his report gained firm political support. There is no comparable support today. While Secretary of State Robert Jenrick has indicated broad interest, other figures within the Conservative Party are pushing for the nirvana of deregulation, the short-term case for which has been strengthened by the need to rapidly revive the economy after Covid-19.