Five months after his election as mayor, Marvin Rees revealed an ambition which had never been mentioned in his manifesto – to encourage tall buildings in Bristol.

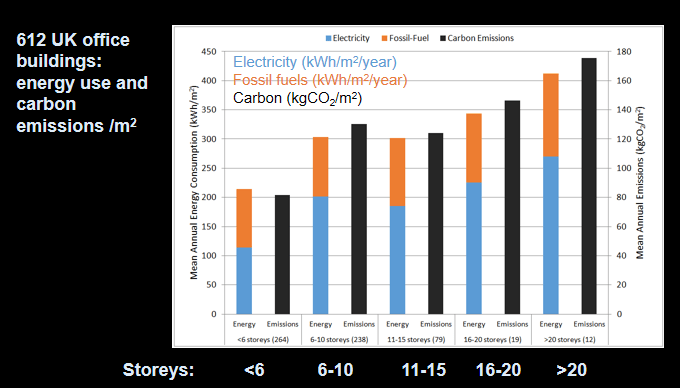

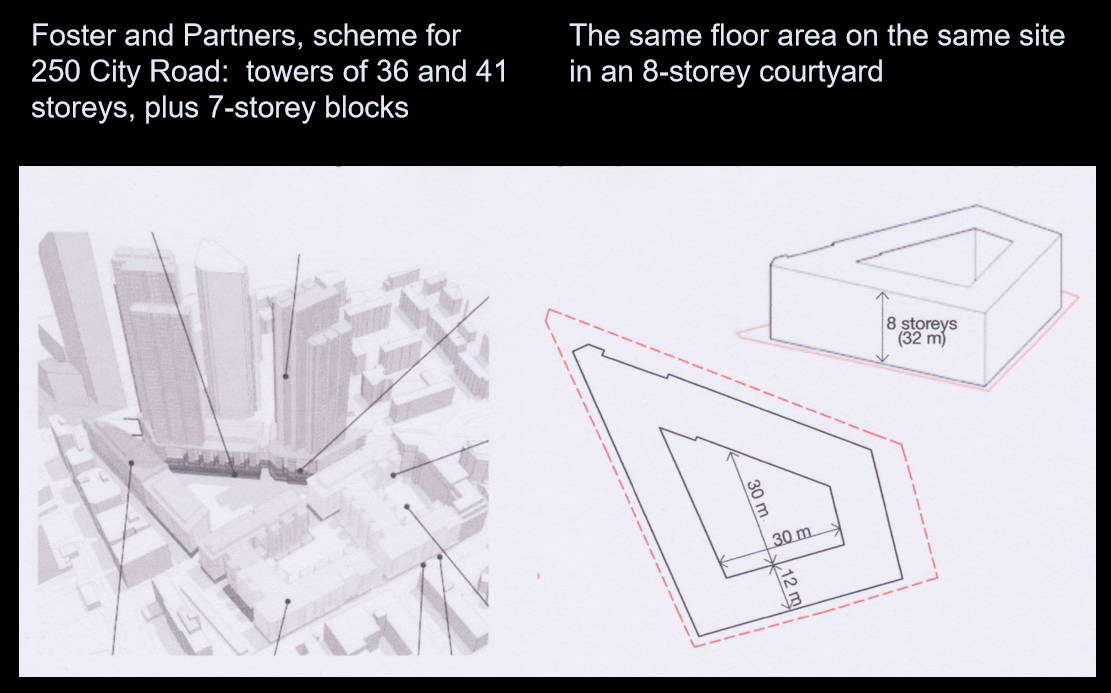

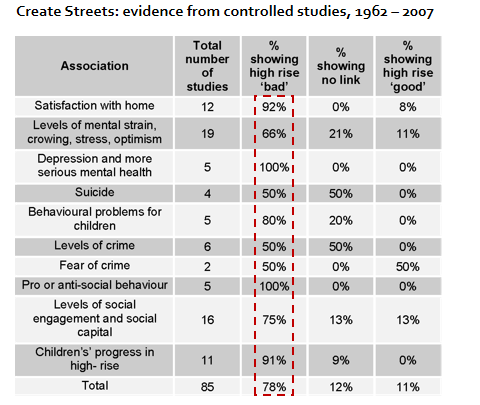

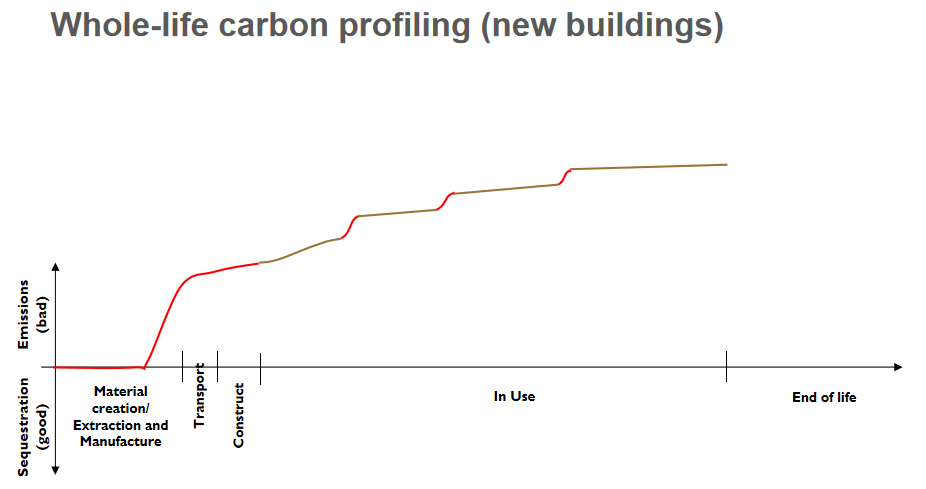

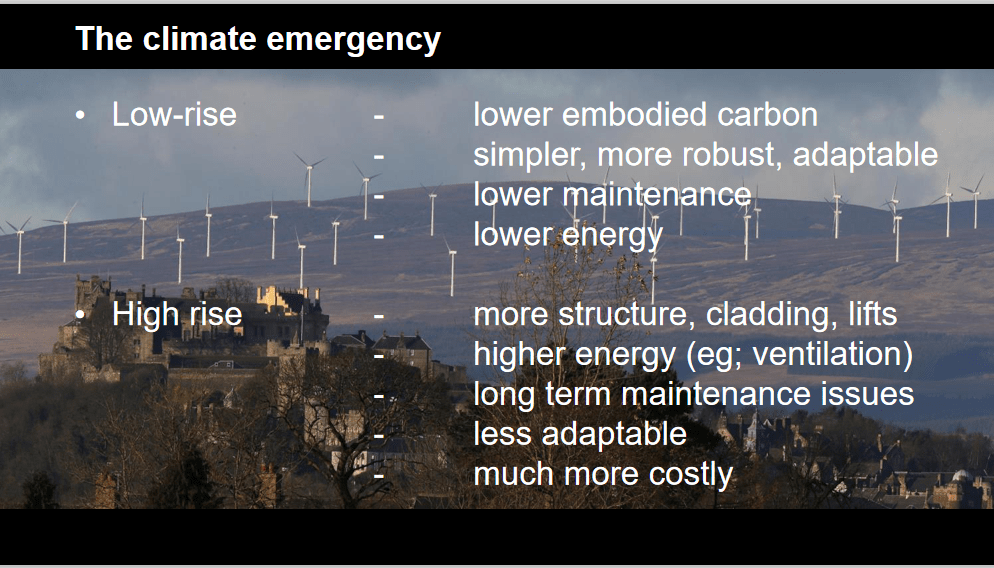

Since then it has been a continuous story of building. Rees, who has little aesthetic sense, has decided that he knows the answers. The answer is to take a beautiful town, with a distinctively low-rise topography (like so many beautiful continental cities – Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Munich, Toulouse and many others) – and to transform it by filling it with skyscrapers, like hundreds of third world cities. Never mind that its present topography serves it perfectly well. It is rich, it attracts talent, and attracts tourists, which it will no longer do when it has been transformed into a high rise city. Never mind that you can build just as densely in mid-rise cities as you can by building high (the two densest city centres in Europe are Paris and Barcelona). Never mind that people are less happy living in tall buildings, less sociable with their neighbours, and that mothers and children find them particularly difficult to live in for lack of places for their children to play. Never mind that tall buildings are much more expensive to build so will probably mostly be bought be foreign buy-to-let investors (as in London), that they are much more damaging to the planet and less sustainable both in construction phase and in ongoing phases. Low rise buildings have lower embodied carbon, are simpler, more robust, more adaptable, and are lower maintenance and consume less energy. High rise buildings have more structure, more cladding (e.g. ventilation), greater long term maintenance issues, are less adaptable and are much more costly.

Bristol is the second richest large town in England after London and the university cities. It is already a densely-inhabited town, and on an average weekend it is sparkling with life. It is recognised as an attractive city, and from its centre you can see the green hills and its many views. But no, insists the Mayor, we have to disconnect our citizens from the sky and overwhelm the traditional elements of the city which we value so much. After the Mayor is done with it – without consulting his citizens – Castle Park will be completely in shade and surrounded by high rises on all sides That is a good thing? Bedminster will also be overwhelmed by high rises. And now they are starting on Spike Island and Ashton Gate!

All these disadvages of high rises are known, they are part of the common understanding of what is taught on urbanistic courses (understood by most people except Marvin). But high rises must be built, because the glory of Marvin requires it!

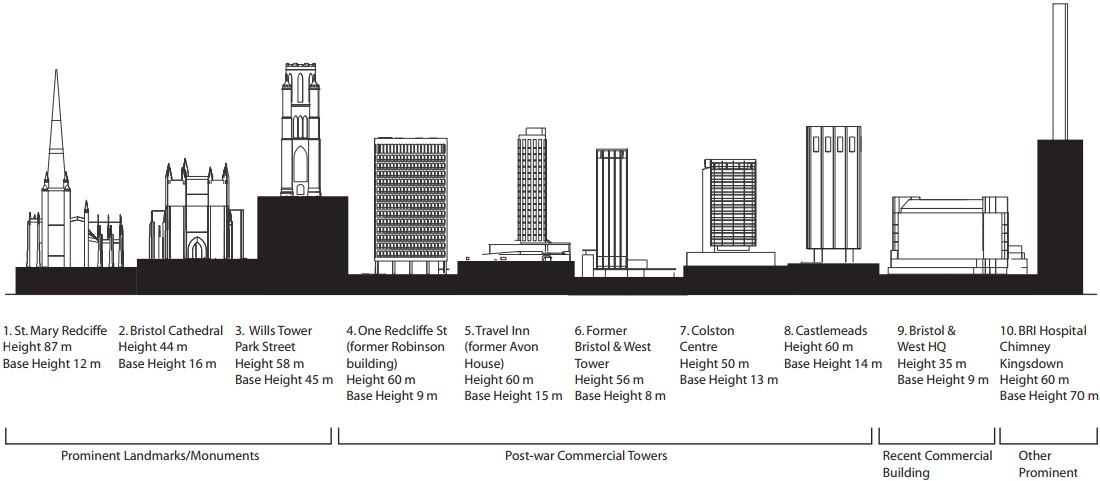

Here are the tall buildings that Bristol now faces:

The City Centre

Rupert Street Car Park. (Developer: Student Roost. Architect: Alec French)(Pre-App)

- Two towers of 20 and 18 storeys, 400 car parking spaces, 151 sq m commercial space, up to 249 co-living units (of which 20% would be affordable) and 328 student rooms.

- Would replace the NCP car park, which a writer in the Architects’ Journal considers “a giant of post-war architecture”, and the C20th century society has applied to be listed.

- Bristol Civic Society say: “Applying Bristol Byzantine to a building so much bigger than the buildings the Victorians built, with a completely different scale and rhythm, seems inappropriate.”

Premier Inn (Developer: Olympian Homes)(Pre-App)

- Two towers – a 28-storey tower with 445 student beds, and an 18-storey co-living tower with 136 rooms (the taller tower would be two storeys higher than the 26-storey Castle Park View tower).

- Previous owners Whitbread have sold to Olympian Homes. They will rename the area ‘St James Square’.

- The developers claim that rebuilding would use much less carbon than refurbishing the current 20-storey Premier Inn, but have not given details of the assessment.

- Bristol Civic Society: “In our view the proposed replacement buildings are far too tall for this site and, indeed, for any site in Bristol. We do not accept that any development should be any higher than the existing Premier Inn.”

Goram Castle Park (Developer: Council via Goram Homes; Architect: Groupwork and McGregor Coxall) Pre-App

33 storeys, 375 flats. of which 12% (75) will be affordable.

It is worth quoting the Civic Society response at length: “The Society objects very strongly to this development proposal...

- “Assault on Bristol. At 33 storeys the Society considers that the proposal is a fundamental assault on the appearance of the city and on its visual traditions.

- “Impact on the Floating Harbour. The Society emphasises the inappropriateness of this waterfront location for a tall building. The Floating Harbour is a defining feature of Bristol, and other new developments have reflected the scale and massing of the former warehouses and industrial complexes.

- “Impact on Castle Park. The proposed development will have a very significant, and highly negative, impact on Castle Park. There will inevitably be issues of overlooking and of overshadowing

“The Society wishes to stress that tall buildings like this are inherently unsustainable and carbon-consumptive.”

The Galleries Owners: La Salle; Developers: Deeley Freed + La Salle Investment Management. Architects: Alford Hall Monaghan Morris (Pre-App)

- 28 storey tower, with 240 housing units; 180 other housing units facing the park (11 storeys); 30 housing units facing north (5 storeys) (20% of the total housing will be affordable); 300 hotel rooms (12 storeys), 800 student units (15 storeys); 5,200 sq. m. of retail, and 22,000 sq. m. workspace units (10 storeys), 200 parking spaces.

- Significant public realm, open 24/7 (35% of site), outdoor seating, open to cyclists and pedestrians. But will the public realm have sufficient sunlight?

- Active frontages throughout. Lots of small retail units (which are more viable than bigger stores nowadays). Green on the roofs.

- The Galleries had a 35% drop in footfall from pre-pandemic levels – unviable.

- The development has the Frome River under it – challenging! (see video)

- The 28 storey height of the tower will cast significant shadow on Broadmead.

- Planning Application expected end-2023, but the new site is not expected to open until 2027 at the earliest.

St Mary le Port Owners: Federated Hermes, and Aviva Investors. Freeholds: Bristol City Council. Developers: MEPC; Architects: FeildenCleggBradleyStudios (21/03020/F)

- Three wide buildings of 8-9 storeys, very ugly, with 28,000 sq. m. of office space, and retail space at ground level.

- Huge controversy: strong opposition from Historic England, the Georgian Group, 20th Century Society, The Conservation Advisory Panel, Ancient Monuments Society, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

- The Bristol Civic Society asked planning ministers to ‘call in’ the plan.

- Refused on grounds that the decision was a local issue.Questions have arised about the relationship between the Friends of Castle Park, a local group whose support for the development swayed the Councillors, and the developers.

- Approved: 9 September 2022

Old Market

Castle Park View (Developer: Linkcity/Bouygues; Architect: Chapman Taylor) 17/04267/F Built

- 26 storeys, 375 flats, 20% affordable, run by Housing Association Abri

- Site was within the Old Market Quarter Neighbourhood Development Plan (OMQNDP) area, but the requirement to consult OMQNDP was ignored by developers and council.

- Old Market Community Association retelling here

- Completed: 2022

Gardiner Haskins (Soapworks) (Developer: First Base) 20/01150/F

- 20 storeys: 250 apartments, 20% affordable, and 154,000 square foot offices.

- The Council’s own City Design Group objected to the (very similar) original plan: “Development scale is grossly excessive, the massing clumsy and overbearing, and the impact on the listed buildings is significant and negative.”

- Objections came also from Bristol Civic Society, Historic England, and Old Market Community Association.

- Approved: April 28 2021

Redcliffe

Temple Back Former Fire Station Developer: Cubex (19/01255/)

- 16 storeys at highest point. 300 buy-to-rent homes, 20% affordable + office space for 1,500 people.

- Objections from the City Design Group, Historic England, and Urban Design Forum, but officer recommended approval.

- Coopers Court (10 storeys), next door, built by the same developers, will be run by the social housing provider Abri.

- Approved in December 2019, to be completed in summer of 2023.

Redcliffe Quarter (Owner: Grainger) 21/02574/F

- 7-19 storeys across 5 blocks, 374 private build-to-rent flats, 94 affordable flats, 6 commercial units

- This is a vast building, mercifully reduced in height from 21 storeys to 19 storeys.

- Site was originally owned by Change Real Estate and Madison Cairn, sold for £128m to Grainger, who lowered the height of the tower and raised the height of the other buildings.

- Permitted on 14 Dec 2017. This is a massive development.

Canningford House, 38 Victoria Street Bristol BS1 6BY (22/05268/F) (Architect: Stride Treglown)

Rather ugly 8-storey office block, most of the height is on Temple Street, the fron retaining the line of Victoria Street

Clifton

New University Library (20/00433/F)

- 36 m tall, taller than Senate House opposite it

- Some people admire the building, but from a distance it will add to the impression that Bristol has become a collection of characterless modernist boxes.

- Bristol Civic Society: [While]”The Senate house, the Wills Tower and the Wills Physics Laboratory create architecturally sophisticated outlines on the skyline…The Library would be an extremely large white masonry slab whose outline contrasts to its disadvantage with the outlines of the other skyline buildings.”

- Permitted: 6 Oct 2021

Silverthorne Lane conservation area

Student + residential buildings + school on Silverthorne Lane (Developer: Square Bay) 19/03867/P and (revised tall building of 16 storeys, Plot 6, Studio Hive) 22/05155/F

- 17 storeys at the Eastern end of a long strip consisting of student rooms, homes, a school and research spaces

- East: 706 student bedspaces, revised design of this very tall building is better than the first very ugly design, but still too tall

- Middle: Oasis Academy, 1,600 place secondary school

- Middle: 371 homes by Studio Hive, max 13 storeys, of which 71 affordable

- West: research spaces

- Heights ignore the advice given in the Temple Quarter Spatial Framework (5-8 floors)

- The Environment Agency objected on flooding fears, a public inquiry was held (May 2021), the Minister of State for Housing gave go-ahead (2022-04-14)

- Initially permitted on August 6 2020, Plot 6 revision still pending.

10 and 12-16 Feeder Road, (Developers: Summix; (19/01881/F)

- Four buildings -14 storeys, and then 5, 7 and 8 storeys with 595 bedspaces.

- Very tall in the context; blocky and ugly.

- A Planning appeal was allowed on 8 March 2022, overuling the flooding-related planning refusal of 25 February 2021, on the view that flood risk is minimal and that any harm to heritage assets is less than substantial and does not outweigh the scheme’s benefits.

Chanson Foods site, Avon Street. Owners: Victoria Hall Management Limited (VHML); Architects: Chapman Taylor (19/02664/F)

- 13 to 8 floors, with 471 student bedspaces, arranged around central courtyard, stepped down to two storey ‘hub’ building providing student facilities.

- Chapman Taylor were architects of the very undistinguished Castle Park View.

- The Council’s City Design Team considered that the proposed scale of the

development to be unacceptable and recommend a height parameter in the range of 6 to 10 residential storeys. The officer’s report claimed that the Bristol Civic Society was happy with the heights, which was untrue.

40-46 Albert Road Developer: Avon Capital Estates; Architect: AHHM (22/06014/PREAPP)

- 17-8 floors, with 472 bed purpose built student rooms

- Ground and lower ground floor uses: reception area, flexible commercial spaces 499 sq.m., plant and cycle storage.,

- Would enlose the river in a canyon of tall buildings.

Mead Street. Developer: DTZ Investors; Architect: Sheppard Robson.

- 1,500 new homes.

- Eight to nine storeys, damaging views of Totterdown.

- 40 per cent of the site will be green space. A central green will be the public heart of the proposal, with lawns, play areas, outdoor gym, community gardens and market spaces

- There will be a 2.5 m segregated cycle lane within the development

Temple Island

Temple Island student accommodation (Architects: AHMM)

- 22 storeys, 16 storeys and 9 storeys (a little lower than original proposals) housing 953 students

- Historic England find the scale and height OK, but judge the buildings to be boring “unrelieved monoliths, with little sense of refinement in their detail.”

- Permitted in December 2019.

Harbour

Baltic Wharf (Developer/Architects: Goram Homes; Builder: Hill) (21/01331/F)

- 150 homes of which 66 (40%) affordable. There will be 1,2 and 3 bed flats in buildings of 4-6 storeys.

- 79% of all homes will be dual aspect. 89% of apartments will have direct or partial views towards water.

- All will meet national space standards. There will be future connection to BCC’s heat network.

- While 6 storeys may not seem tall, in the context it is. Historic England say: “We reiterate our belief… the scheme should be reduced by a single storey.” Bristol Civic Society made the same request. Goram replied that this would sacrifice much of the affordable component.

- The buildings are slightly raised to incorporate flood measures, but there have been six objections on flooding grounds by the Environment Agency because the plan poses “a significant risk to life”.” However Bristol’s Principal Flood Risk Officer Matthew Sugden has withdrawn his objection.

- No decision yet. Application made on 16 March 2021.

Wapping Wharf North (Developer: Umberslade) (pre-App)

- 12 storeys at the west (Harbour) end, with 4 blocks sloping down to 8 storeys on Wapping Road . The 12 storey block would accommodate restaurants on the terraces.

- Above the ground floor, there would be 240 apartments of varying size, but predominantly one and two bedrooms.

- The site is between Museum Street and Rope Walk behind M-Shed

- If anyone finds the result beautiful, I am amazed. The damage to one of Bristol’s prime assets – the harbour – which pulls the whole town together, and is such a source of pleasure for strollers at weekends, would be incalculable.

- An unfortunate precedent for future proposals in the harbourside area.

Former Peugot site, Clarence road. (Developer: Dandara Living; Architect: Stride Treglown) (Pre-App)

- 10 buildings: 19 storeys, 10 storeys, then 9, 8, 6, 6, 5, 5, 5, and 3 storeys. 412 flats.

- A hideous “welcome to Bristol”, the development will sit on the roundabout at the beginning of Bath Road, almost opposite the station. It is a trafficky, noisy, and polluted location.

- The immediate environment is now mostly low-rise, but Dandara seek to justify the heights by reference to the Temple Island Development Site with up to 24 storeys and Soapworks up to 20 storeys.

Plot 3, Temple Quay. (Owner: Homes England; Developer: IKB Developments: Architect: Sheppard Robson) (22/05998/F;

- 3 buildings of 10 – 6 storeys: a 234-room hotel; a 168 apart-hotel; and a 108 room build-to-rent residential block (with 21 Affordable Private Rented units (20% of total residential units)

- This is a key site, immediately visible on exit from the northern (future main) entrance of Temple Meads Station.

- Revised to good effect after comments from the Council to improve visibility of the Eye, the Floating Harbour, and Temple Meads Station from Valentine Bridge. Undecided

Assembly (Developers: Bell Hammer, AXA; Architect: Allford Hall Monaghan Morris; Builders: Galliford Try) (No code number)

Completed in July 2021, Building C has 14 storeys and is let entirely to BT, accommodating up to 2,500 employees. Building A (13 storeys) and Building B (7 storeys) will both be finished in Spring 2023.

1 Passage Street (Owner: LPPI Real Estate Fund; Developer: Knight Frank Investment Management; Architect: AWW) (21/06933/F)

- 13-storey office building, next to the Cheese Lane Shot Tower, which replaces a rather uninteresing building.

- Its height obstructs the view of the 19th century Generator Building and St. Philip & St. Jacob’s Church (13th century)

Temple Island – eight blocks (Architects: Zaha Hadid) (Pre-App))

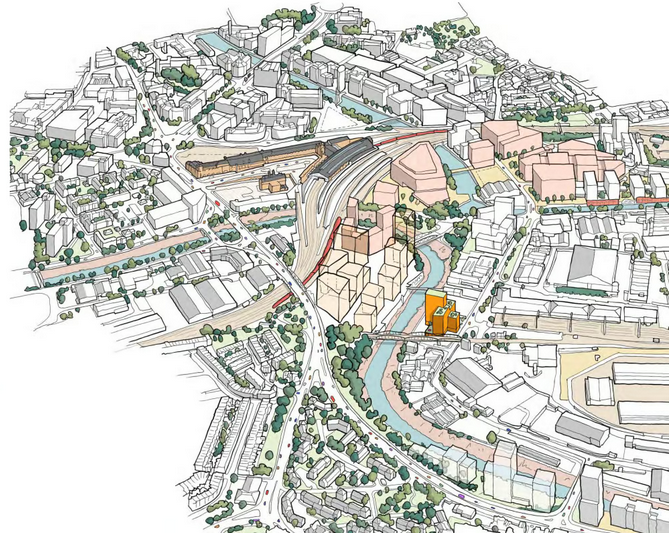

- The former Arena site: 8 blocks of up to 24 storeys. On the southern side, there will be 5 residential towers (31.40m to 82.60m) containing 550 new homes (including 220 affordable). The back row will contain a conference centre and a hotel (with 345 rooms) (56.80m tall), and 2 office blocks (35m, 47m).

- Featureless, ugly towers. Very poor access to the area.

- Legal & General will invest £350m, and will be guaranteed rent on the office space for 40 years. In return, Bristol City Council will spend £32m getting the plot ready, including sorting contamination issues.

- In 2021, Rees said that over 25 years the city would get about £850m of gross added value, compared to about £300m from an arena, and that the L&G plans would generate about three times the number of jobs.

- Bristol Civic Society: “Bristol Civic Society was disappointed with the proposals for this important site. We cannot support the preapplication plans as they stand.”

Land on the North side of Gas Lane (Owners/Developers: Watkin Jones and Merrion Group; Architects: AWW (21/06761/F)

- 8 to 9 storeys; 299 student rooms arranged in a triangle, one side taller.

- Given height of the buildings, little light is likely to penetrate the triangular site, creating an unattractive, shady courtyard.

- The building is rough, ugly, and would present cliff faces to Freestone Road, Gas Lane, and to the north/south route adjacent to the east end of the development.

- Approved: 6 March 2023

Freestone Road. Developer: Tiger Developments; Architect: Chapman Taylor (preApp)

- Four buildings of eight and nine storeys

- 204 bedrooms (?) in four blocks linked by a series of footbridges.

- The buildings’ heights have been revised upwards, meaning (Civic Society) “It would protrude much further above the railway embankment resulting in a grim, grey wall when viewed from the north and from trains approaching or departing from Temple Meads.” It would also “spoil the ambience of Dings Park, overbearing it and possibly overshadowing it particularly at darker times of the year.”

Land South of Freestone Road and west of Kingsland Road Owner: Unite Students; Architect: Alex French) (22/06050/F)

- 16 storeys on the northern side, stepping down to 10 storeys.

- 600+ bedspace student accommodation plus public spaces around existing locally listed Kingsland House and between the new buildings. Active frontages with commercial space along Kingsland Road.

- The height would be extremely harmful to the character of the area and to the light and ambience of Dings Park. The justification for these heights in the Design and Access Statement is frankly ridiculous, contradicting all advice.

- Bristol Civic Society: “The Society considers that the maximum height of buildings should be similar to the 8 storeys proposed by the university for the south side of Gas Lane and respect the height of the student housing proposed for the north side of Freestone Road.

- Application made 22 December 2022 but not yet considered.

Bedminster / Windmill Hill

Bedminster (below) is the city’s most contested area. The council made informally clear to developers that the area should have tower blocks. Developers piled in chaotically and without co-ordination, bidding up land prices, no master-plan having been developed by the city. Eventually consultants Nash Partnership were called in to master-plan, aggressive heights having been put into the Urban Living SPD and into the Local Plan.

A residents’ group, Windmill Hill and Malago Community Planning Group (WHaM), has continuously challenged the proposals. Some heights have been reduced, some designs have been improved, but it is a wearysome process with developers appealing rejections and, when the appeal is refused, coming back with new proposals only marginally different from the original.

Pring Hill Site / Malago Road (Plot 1) (Developer: a2 Dominion ? Watkin Jones) 19/00267/F

- The original 12 storey application was recommended for refusal by officers and was in fact refused in September 2019 – so an appeal was launched

- In April 2021 the appeal was dismissed.7% affordable (40 out of 590)

- Refused 6 September 2019 No new application has yet been made.

St Catherine’s Place (Plot 2) (Developer: The PG Group and Firmstone)

- A 14 storey application was approved in March 2021.

- Committee members followed BCC officers’ recommendation to refuse the original application, despite a height reduction from 22 to 16 storeys. An appeal against this refusal was dismissed in February 2021.

- 0% affordable out of 180 flats

- Granted 1 October 2021

Dalby Avenue (Plot 3) (Developer: Watkin Jones) 20/05811/F

- Multiple buildings up to 9 storeys

- 0% affordable (out of 837 student units)

- One of the most worrying developments, given its multiple impacts – but with City Design Group input, cladding changes and a little height reduction has improved it

- Plans submitted in December 2020, decided 23 December 2021. Construction on Plot 3 started in spring 2022 and is due for completion in September 2024.

Little Paradise Street (Plot 4a) (Developer: Dandara) 18/06722/F

- Permitted October 2020, despite strong City Design Group reservations over height

- High proportion of single-aspect flats (64% in private, 72% in affordable units), and worries about daylight 6% afforable (21 out of 316)16 and 14 storeys

- Construction on Plot 4a started in spring 2022 and is due for completion in September 2024.

Triangle between Malago Road, Whitehouse Lane, and Hereford St (Plot 5) (Owner: Council; Developer: Dandara) (21/05219/F)

- Still in consultation – three buildings, with the largest up to 10 storeys, yielding 105 affordable homes our of 350

- The buildings wrap around Bedminster Green.

Totterdown

Totterdown Reach Bath Road (“The Boat Yard”) (Owner: Clarion; Architects: Feilden Clegg Bradley) 18/04620/F

- 17 storey tower, plus 3 other blocks (7,6 and 3 storeys) giving a total of 152 flats, 30% of which will be affordable.

- At 65 metres, the Tower will have an unmissable impact on the views to the north for many Totterdown residents, dominating the local character of the Bath Road and Totterdown Bridge.

- This ugly set of buildings – shown off by Marvin Rees to a visiting Keir Starmer as evidence of his magnificant achievements – have had an accident-prone history. In July 2022 developer/builders Mid Group went backrupt, and their workers were fired. In January 2023 part of the embankment beneath the development was reported sliding into the river. The developers claim that this does not affect the buildings’ stability. But in 2019 warnings were already given in a geotechnical assessment made of the site by Arup.

- Bristol Civic Society has raised safety fears about the high rise tower, which has just one escape route.

- The development is sited above a busy junction on an arterial road with the added nuisance of industrial noise from the north side of the Avon River.

Approved March 2019

122 Bath Road (Developer: P. Yates) Architect: Robert O’Reilly. (21/04096/F)

- 5 storeys high and 32 apartments, some single aspect, of which 30% affordable, or 9 apartments. The original application was for 9 storeys, far exceeding Bristol City Council’s own guidance on the density of homes per hectare. The local plan recommends 20 units only.

- Objectors included ward member TRESA (Totterdown Residents and Social Action) The Windmill Hill and Malago Community Planning Group (WHAM), the Conservation Advisory Panel and the Civic Society.

- Although the new design is less ugly and less tall, the Civic Society has maintained its objection, on grounds of no ground level outdoor space and the noise and pollution from the heavy traffic on Bath Road.

- The planning officers supported the application.

Applications: Original: 27 July 2021; Revised: 22 Feb 2022. No decision yet

Ashton Gate (Owner: Ashton Gate Ltd; Architects: KKA).(pre-App)

- 14 storey residential tower and nearby office, reduced from 18 storeys

- Permission will be sought for a sports and convention centre (4000 seats), a 230 bed hotel, 92,000 sq. m. of offices (9 storeys), 140 one and two bed flats in 6, 7 and 14 storey blocks and 540 space multi-storey car park (7 storeys) on land adjoining the stadium;

- These tall buildings will obviously impact very sensitive city views.

Lawrence Hill

Barrow Road (Developer: Galliard Homes) (pre-App)

- 18 Storeys and 10 storeys (next to the Kingsmarsh House high-rise block) plus town houses. Will overshadow nearby houses.

- Former Mecca Bingo Hall and Pure Gym warehouse building located between St Philip’s Causeway and Lawrence Hill High Street.

- Says campaigner Eve Bergsoul: “This area already has a large number of tower blocks and tower blocks are conducive to social problems. High-rise living is not the best kind of living and we’re being put upon to just accept this.”

Broadwalk Shopping Centre Owners: BDS Development; Developers: Pelican; Architect: Keep. (22/03924/P)

- What a drama! An application for a 12 storey shopping and living development to house 850 people in an extremely crampted space was initially refused, after prolonged and skilled campaigning by local, Laura Chapman.

- A week later the application came back to committee, notionally to firm up the reasons for refusal. But something odd happened.

- All the applicants’ supporters were there. No campaigners were. Why? They had been told refusal was a certainty. But the Labour councillors changed their vote – and the planning application was accepted.

- The perception that there had been a stitch-up was inescapable. Richard Eddy, the Conservative chair of the committee, defended the Committee’s decision to approve planning permission, slaiming that every public comment was taken into account, and promises of extra affordable housing from developers had tipped the balance in favour, and that all processes were followed properly. He persuaded few people.

- Laura Chapman is raising money, so far remarkably successfully, to launch a judicial review.

- Application originally submitted on 11 August 2022, approved 5 July 2023

Commentary:

Marvin Rees’ desire to bring more tall buildings to Bristol meant rewriting the city’s planning law (see account of how it was rewritten). To do this, Rees appointed councillor Nicola Beech, previously a developers’ PR, as head of planning. She pushed through a new Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) “Urban Living” in 2018 to replace the 2005 SPD (which had protected Bristol from tall buildings (see comparison of new SPD and previous SPD). This new document then had to be consulted on, by law. Residents, ordinary citizens, architects and amenity societies, in the largest response to any consultation in the history of Bristol, overwhelmingly rejected tall buildings. This response was ignored by Rees and Beech.

While densification of city centres is often good, helping make cities walkable and helping support public transport, the densest cities in the developed world are not US cities with towering high rise centres, nor UK cities following suit like Leeds or Manchester, but historic mid-rise continental cities like Barcelona and Paris.

These dense European cities are more beautiful, more sociable, pleasanter to be in than the US cities. They have gentle mid-rise centres, connected by good public transport (typically trams). So why are we rushing to go high when it is not necessary? The argument ‘for’ – which pleases developers – is based on false logic, as has been eloquently argued in Bristol before the Bristol Civic Society by UCL’s Professor Philip Steadman, Create Streets’ David Milner, and Bennetts Associates Rab Bennetts.

Mid-rise densification can house as many or more residents (see Steadman), is more sustainable because it uses less carbon (see Bennetts), makes residents happier (see Milner), and will produce many more affordable housing units, because it is less expensive to build per square metre. It is also more beautiful which, research suggests, in the longer-term is likely to increase Bristol’s prosperity by attracting talent to the city.

Sources of information on planning applications:

Centre / Castle Park / Redcliffe: No organisation tracks applications in this area. The best source is the Bristol Civic Society (BCS) Planning Issues Status page, and Planning Issues, and Planning Archive. There is also a BCS twitter, which frankly needs more effort: @BristolCivicSoc

Bedminster. The best source is the WHaM site and, for keeping up to date, the WHaM Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1511895115798962

Totterdown / Bath Road. A source is Totterdown Residents Environmental and Social Action (TRESA) , though it is primarily social. More useful for keeping up to date is TRESA’s twitter: @TRESAci

City-wide: The best source is the Bristol Civic Society. The Neighbourhood Planning Network has an excellent Current Topics page. Specifically on high rises: https://www.facebook.com/groups/169400953696154.