“Should Bristol become a high rise city?” The conclusion of the three expert speakers at the Bristol Civic Society’s March 5 event at the Arnolfini theatre was an unambiguous no. Tall buildings are bad for the environment, and bad for happiness. Matthew Montagu-Pollock reports.

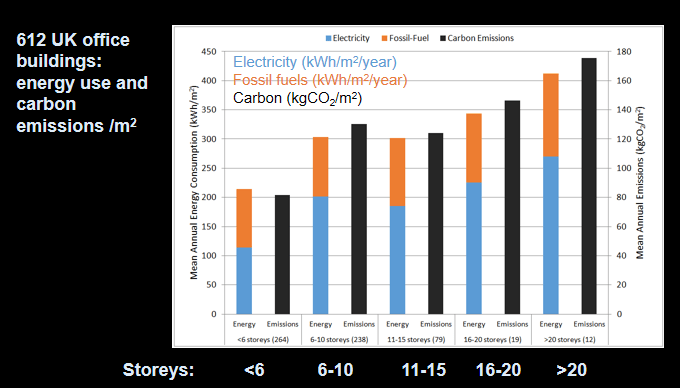

With lots of graphs and charts, this was a research-heavy evening. Much of the information was surprisingly new – one wondered why no-one asked these questions before. First up was Professor Philip Steadman of UCL, an expert in buildings’ energy usage (PDF version of talk). Steadman has compiled an extraordinarily large data set of 612 UK office buildings, new and old, large and small, airconditioned and naturally ventilated, to compare their energy usage, using actual energy consumption figures. This had not previously been done before anywhere in the world.

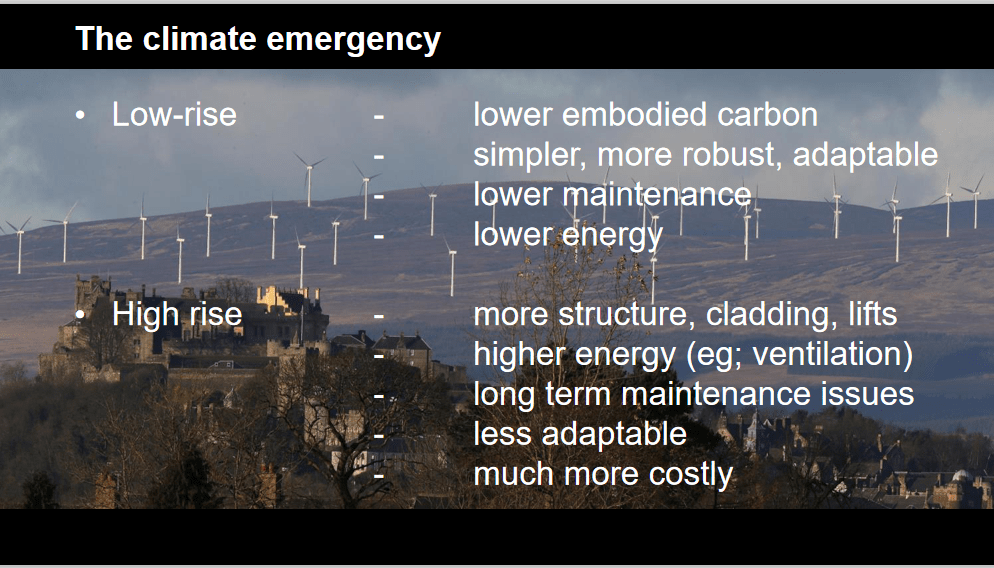

The results were a big surprise. Tall buildings use dramatically more energy than other buildings on an ongoing basis, in fact 100% more energy per square metre. Their carbon emissions per square metre are more than twice as large. Tall buildings in fact never use less energy, except in the case of one Foster building where the architect has effectively encased one tall building inside another, obviously a highly expensive undertaking. Steadman was surprised by this result, because existing theoretical models of energy usage forecast that tall buildings should be mildly more energy-intensive, using around 15% extra energy. Conclusion: the computer models that architects use to forecast ongoing energy use are highly misleading, when tested against real-world observations.

What is the reason for the extra energy use? Lifts only use 3% of a tall building’s energy, so they don’t explain it. Maybe the air-conditioning? No – the effect survives even if you separate out non-airconditioned buildings. So what is the reason? Though this is speculative, the most likely reason appears to be that tall buildings are exposed to cold air and wind in winter, and heat in summer, because they stick up. So they need more heating and more cooling.

Tall buildings also use more “embodied energy”, I.e. energy consumed during construction, before the building is brought into use. A group in Australia looked at embodied energy and height in office buildings, studying two low-rise offices on 3 and 7 storeys, and two high-rises on 42 and 52 storeys. On average, the embodied energy per square metre of floor area was 60% greater in the tall office buildings. So their construction has an extremely high environmental impact in terms of energy and carbon use.

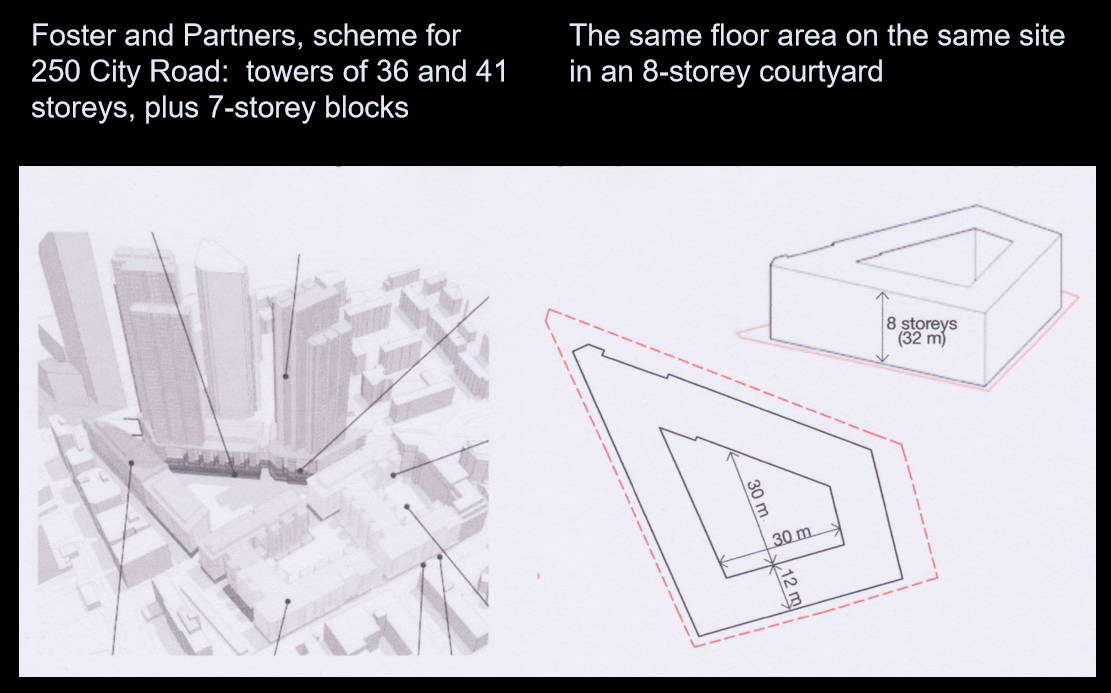

We are often told that to densify urban space we need tall buildings. But this too is an illusion, argues Steadman. Tall buildings’ shadows tend to block neighbouring buildings’ light, so they need to occupy extra space. So in real life the typical mid-rise building has the same Floor Space Index (FSI) as a tall building (FSI = floor area, divided by land area used), I.e. tall buildings do not in practice provide extra density.

This can be intuitively demonstrated by re-arranging Foster and Partners’ 41 and 36 storey 250 City Road scheme into an 8 storey courtyard building. Both schemes would occupy the same land space, and yield the same usable areas, and have the same FSI, even though one is massively taller than the other.

Steadman’s research suggests that:

- Energy usage intensity in UK office buildings increases with height, and is doubled going from 5 storeys to 20 storeys and more.

- Embodied energy usage in Australian office buildings is 60% greater in high-rise than in low-rise.

- Energy intensity also increase with height in UK blocks of flats.

- Computer models of energy use do not appear to predict these effects.

- The densities achieved by tower buildings can generally be achieved in slabs or courtyard buildings of less than half the height.

- Conclusion: Much energy could thus be saved by building lower, without sacrificing density.

Next speaker up was David Milner of Create Streets, an urbanism think-tank founded in 2013 by Nicholas Boys Smith, who was recently co-head of the government’s Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission (PDF version of talk).

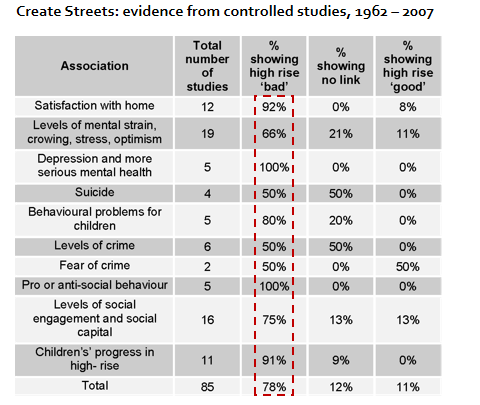

Create Streets are quiet revolutionaries, pioneering the collection and creation of quantitative research, which is increasingly available and, in their view, highly necessary given that architecture and planning largely lack a tradition based on empirical evidence, at least as psychologists or the sciences would understand such evidence.

Create Streets has gathered evidence which looks at how building forms can increase human interaction and happiness. What proportion of health might be derived from the environment? About 40%, according to US research. And what built forms add pleasure, encouraging sociability and happiness, and improving mental health?

- Trees and green – but preferably green in smallish spaces, with private green areas, or areas shared among rather few people (e.g. a small park)

- Streets with no or only slow-moving motorised traffic

- Streets with active facades rather than dead spaces

- Symmetrical buildings, with detailing and decoration

- Views of water

- ‘Traditional’ rather than ‘modern’ building designs

- Buildings with colour

- Small squares rather than large squares

- Green suburbs (though the stress of commuting can completely undo the associated increase in happiness)

- Mid-rise buildings rather than high-rise

Each of these effects is highly supported. Collectively they greatly outweigh income effects. Interestingly, Create Streets’ findings demonstrate the considerable distance between the predispositions of many architects and the tastes of ordinary people (many architects prefer tall and modern building designs, while research shows that than most ordinary people prefer mid-rise buildings, and traditional designs).

The evidence is also clear that tall buildings cause greater loneliness and more depression, are not optimal for children, are associated with social relations that are more impersonal and where helping behaviour is less than in other housing forms. “Crime and fear of crime are greater [in tall buildings], and…they may independently account for some suicides,” notes an important survey by Robert Gifford (2007) quoted by Create Streets which concludes: “the literature suggests that high-rises are less satisfactory than other housing forms for most people.”

Third speaker up was Rab Bennetts, who led us from Le Corbusier’s futuristic vistas to the “international style” of today’s globalised highrise cities, including the social housing of the 60s, and the towers of Dubai, Hong Kong, Panama, and the City of London (PDF version of the talk 3MB).

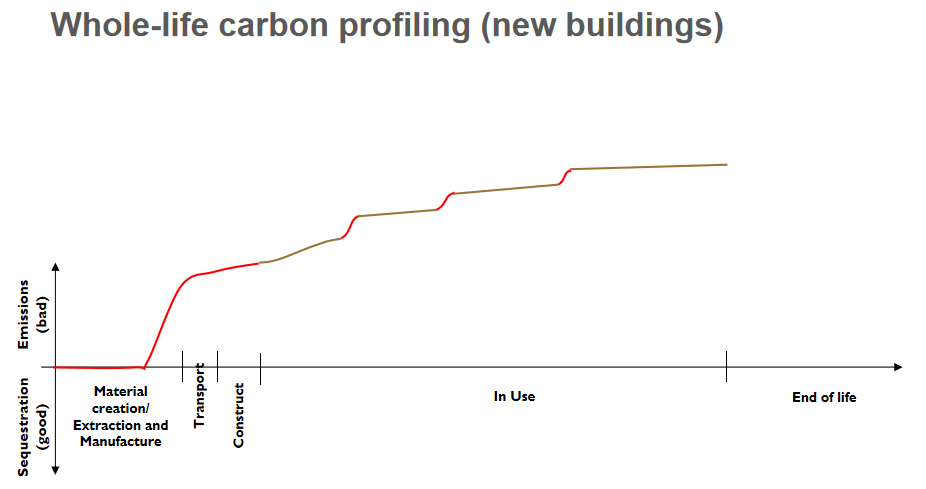

With long experience as the founder of the UK’s leading sustainability practice, Bennetts shared with us the embodied costs of building high. The following image is more or less what a building’s lifecycle looks like, with red emissions when using new materials either to build or maintain a building and brown lines where it’s using energy over time. More of the emissions happen during the construction stage than during the entire working life of the building.

The typical cost of not only the materials but of transporting them to the building site is so large that it could take 50 years at least before even a very ecologically friendly new building actually becomes sustainable.

Bennetts confessed that he himself had not been guiltless. Tasked with masterplanning an Islington canal-side site he had sought to reduce heights and density on the canal by completing the area with a 25 storey building. But as the site was sold on and the design passed from developer to developer the building got taller and taller, setting a precedent for 2 more neighbouring high rises which have since totally overpowered the local environment.

What should be our ambition? To re-use old buildings. To use natural materials which absorb carbon, so as to achieve a zero carbon footprint almost from the word go. Seemingly an almost impossible ambition – but one we should aim for.

Videos of presentations:

Professor Philip Steadman

(PDF version of Prof Philip Steadman’s talk)

David Milner

(PDF version of David Milner’s talk)